Global Value of Music Copyright jumps 18% to a record high of $39.6bn in 2021: could it have been even higher?

8-MINUTE READ

Global value of music copyright now $39.6bn, with streaming making up 55% of the total.

Copyright is now worth 40% more than when CDs peaked in 2001, with labels seeing 65% of all the value and publishers at 35%.

Streaming has made music more global in culture, yet more American in commerce. Since the launch of Spotify in 2011, US share of the record business has grown from 26% to 38% – and the strong dollar can only increase its dominance.

Pick up the pieces

In the increasingly competitive attention economy, music periodically needs to take stock of its true worth. The annual task of calculating the global value of music copyright enables such an appraisal, looking not just at record labels but also publishers and collective management organisations (CMOs).

To get to the final number, four partly overlapping sources of industry analysis are brought under one umbrella: (i) IFPI’s Global Music Report, (ii) CISAC’s annual Global Collections Report, (iii) Music & Copyright’s analysis of music publishing and (iv), a new addition this year, MIDIA’s estimate of royalty-free music services like Epidemic Sounds. Past editions explain prior methodology from which this year’s calculation evolved: 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2001].

The purpose of this undertaking remains the same: Whether you're investing, operating, or earning from music copyright, you ought to know how much it's all worth – and how each piece of the puzzle is trending. This year we not only have a really big figure to digest, but big improvements in methodology. CISAC, for example, has removed US digital mechanical-rights income (and helpfully revised all prior years for consistency) because the recently formed Mechanical Licensing Collective is not a CISAC member.

Stacking up copyright’s value

In 2021, music copyright was worth $39.6bn – considerably more than the $25.9bn reported in the same year’s IFPI Global Music Report (GMR), and up 18 percent from 2020. The post-pandemic fallout has seen consumer subscriptions and ad-funded streaming continue to soar, whereas business-to-business licensing by CMOs has only partially recovered.

The two most notable changes beneath the headline figure are the explosive growth in label revenues (pink) from streaming and the annual growth of the songwriter CMOs’ collections (in red). Performing right income dominates this segment, and within that general purpose licensing (e.g. restaurants, retail and concerts) makes up a significant share. There’s clear evidence of a post-pandemic bounce back with collections up by almost 10 percent, yet still trailing behind its pre-pandemic 2019 figure.

Global Value of Music Copyright

Source: IFPI Global Music Report, CISAC Global Collections Report, Music & Copyright, MIDIA and Will Page

Fair division?

At face value, copyright has never been worth this much. In my recent publication, Global Value of Music Copyright is bigger now than it’s ever been, I was able to back out a figure for 2001 – the earliest data available. That year, the global value of recorded music was $28.3bn – of that pie, just 23% went to publishing.

The next available data point to compare comes thirteen disruptive years later, (it’s not possible to join the dots on the intervening years). Back then, in 2014, label revenues had gone from boom to bust and were in the trough of the current cycle, whereas publishers and their CMOs reported moderate growth and record breaking collections. As a result of these mixed fortunes, the split of the pie had shifted to 55% labels and 45% publishing.

Roll forward to 2021 (where we exclude royalty free music for consistency) and the pie has grown by 40% since 2001 to reach $39.6bn. But something interesting has happened over that period: the publisher's share has now fallen back to 34% – still up by half on 2001 but well down on the level of 2014. What caused that? The answer is the recovery in consumer spend on music, which traditionally favours labels over publishing. This has been accentuated by the pandemics adverse impact on business licensing, which traditionally favours publishers over labels.

Source: IFPI Global Music Report, CISAC Global Collections Report, Music & Copyright, MIDIA and Will Page

But the great news is the value of copyright keeps on growing. Nostalgia has long been the biggest enemy of the music industry – a misplaced belief that we need to get back to the ‘good old days’ when record labels used to sell CDs to stores by the weight-of-pallet. Nostalgia can mislead and misinform – music copyright has never had it so good.

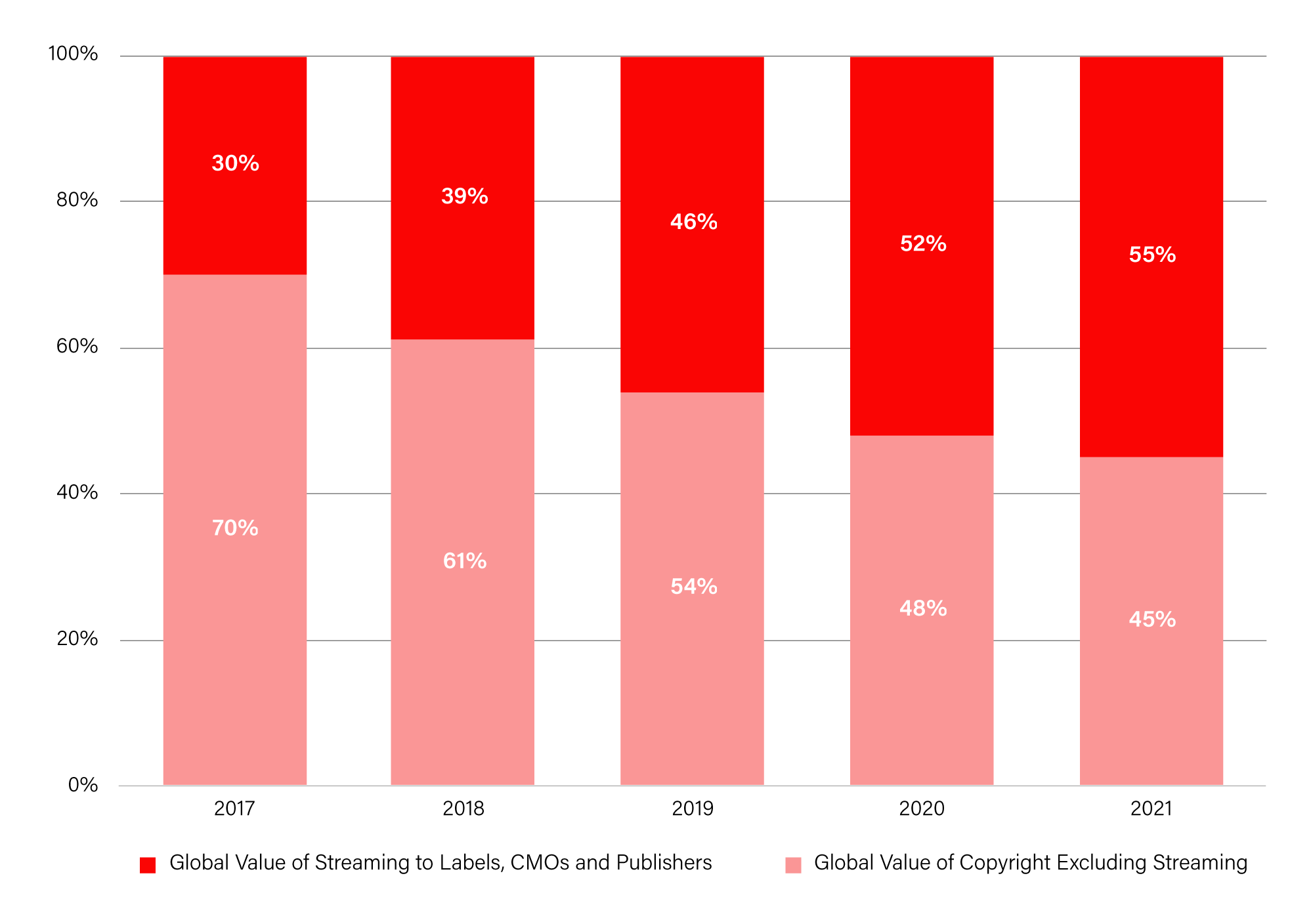

Streaming makes up the majority

Last year, I reported that streaming passed the 50% threshold for the first time, making up the majority of copyright’s value in 2020. This year, streaming continues to make up a bigger share of a bigger pie, despite the partial bounce from licensing concerts and the high street, and now makes up 55%. One trend to ponder: If streaming makes two-thirds of IFPI’s recorded music revenues, yet under a third of CISAC’s global collections (as there are so many more sources of income), will the two converge or diverge over time?

Streaming Drives Copyright’s Global Value

Source: IFPI Global Music Report, CISAC Global Collections Report, Music & Copyright and Will Page

Could it have been $40bn? Should it have been $40bn?

Make no mistake: $39.6bn is a huge figure. It might fall just short of what Elon Musk paid for Twitter, but it's still a damn big figure.

When I first carried out this arithmetical exercise for 2014, the headline was $25.28 billion. Now we’re staring at a number that – when rounded up – would begin with a four! To put that into historical context, this $14.1bn increase in the value of copyright to labels, publishers and their CMOs since 2014 matches the IFPI’s global music report for the same year ($14.1bn). It’s tempting to ask – if it had not been for the pandemic – should it (or could it) have breached the $40bn milestone?

If we look at revenues across a two year time span, from (pre-pandemic) 2019 to the present, we see how performing rights have suffered, by $0.5bn. On one hand, had the world not entered lockdown, and performing rights income had continued growing at a 6% a year, then arguably they would be $1bn higher today ($9.4bn, not $8.4bn), bringing the grand total past $40bn. Yet on the other hand, had the pandemic not happened, streaming may never have accelerated the way it did.

2019-2021 Change in Music Copyright, $m

Source: IFPI Global Music Report, CISAC Global Collections Report, Music & Copyright and Will Page

Royalty Free Music: Adding a New Piece to the Copyright Puzzle

The terms ‘production music’ and ‘library music’ are as old as the hills. Publishers large and small will have a division dedicated to this form of ‘buy-out’ music that can be acquired by users with an upfront payment. However, new entrants like Epidemic Sounds have dynamised the business, offering a subscription-based model to access 35,000 royalty-free music tracks and 90,000 sound effects.

Services like Epidemic have a very different value chain: charging an upfront fee of $1,200-to-$6,000 per track, with streaming revenues from streaming services shared equally amongst creators, and an added ‘fixed pool’ bonus (currently $2m) that's awarded based on the number of downloads. MIDIA, a respected consultancy, estimates ‘royalty free’ music to be worth $250m in 2021, with market leader Epidemic Sounds making up over a quarter of that new pool. The resulting trickle-down economics is impressive: an average individual creator is reported to make $50,000 a year on Epidemic Sounds.

Why bother including the small-change of ‘royalty free music’? Attention economics. Or, as I explain in my book Tarzan Economics: ‘Paying attention is tough these days: attention is a scarce resource and everyone wants more of it, meaning something has to give’. Think of the growth of podcasts in their ‘share of ear’ – if I choose to listen to the latest podcast over a new song, I’m allocating forty minutes of my scarce attention instead of four.

James Cridland, editor of PodNews, notes the average weekly podcast listening to be hovering around seven hours; the equivalent for music streaming is only a couple of hours more. Yet there remains no solution to enable podcasters to license commercial music, meaning the only type of music that this attention-grabbing audio content can currently accommodate is royalty-free (i.e. buy-out production music).

If commercial music wants to win back attention that’s been lost to long-form podcasts, it needs to give up on bringing a horse to water (expecting podcasters to adapt to current licensing complexity) and develop solutions that bring water to the horse (or ‘fight complexity with simplicity,’ to quote Epidemic Sounds). That way, music can compete for scarce attention that might otherwise go elsewhere.

Smoke Signals

In our weekly podcast Bubble Trouble, my co-presenter Richard Kramer, founder of Arete Research, often moves the latter half of our conversations to a ‘smoke signals’ segment, asking our guest to flag those ‘uh-oh’ moments they see coming when they step back from the hype and hysteria, or to bring cringeworthy terminology or metaphors down to size. In light of this research showing that music copyright has never had it so good, it’s prudent to curb our enthusiasm and do a little smoking here.

Dollar dominance

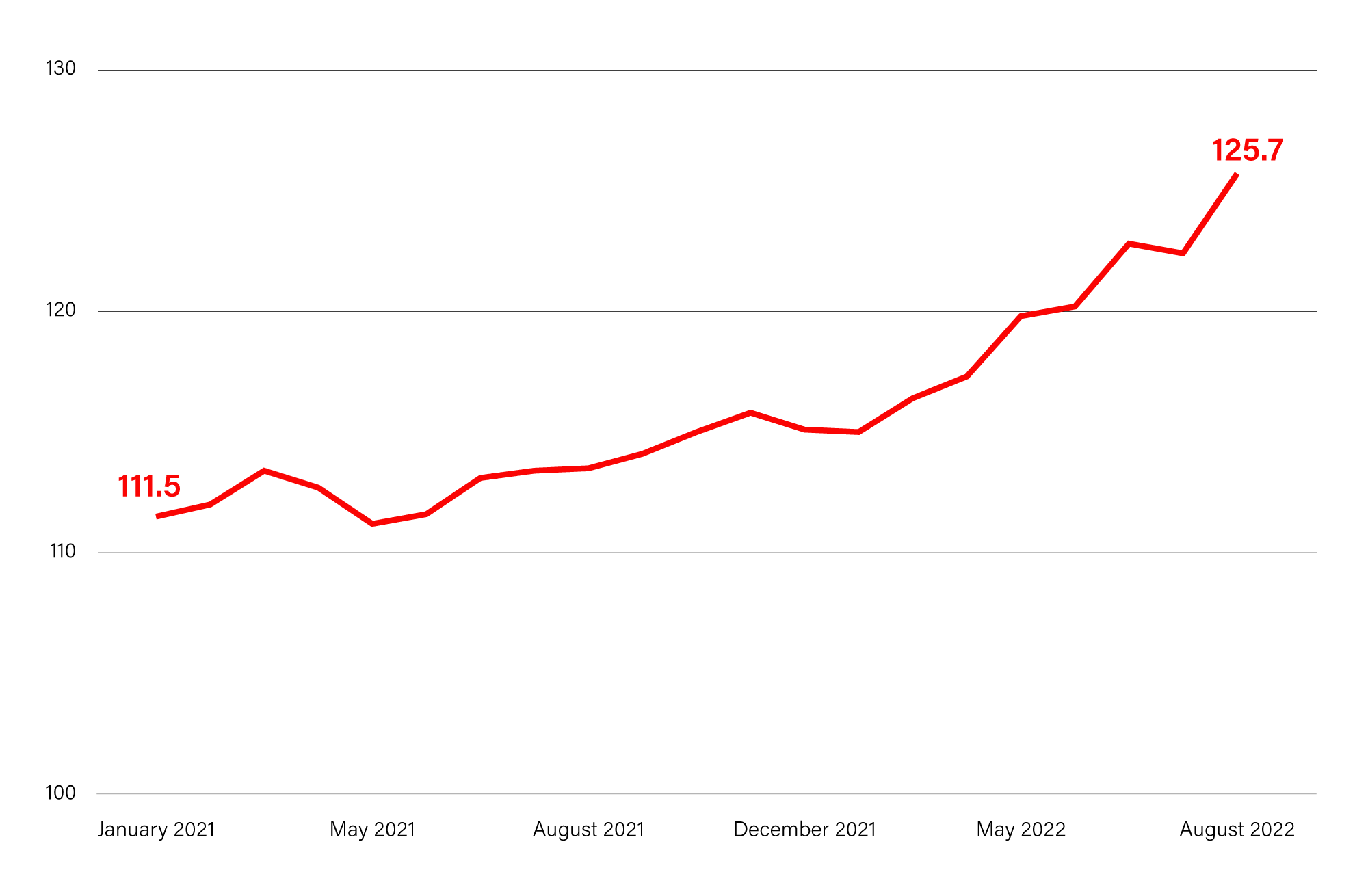

One obvious cause for concern is the economic climate (or, more specifically, the strengthening US dollar and its impact on this global calculation). The St Louis Federal Reserve tracks a US dollar trade-weighted exchange rate which measures movements against a representative basket of currencies. Since January 2021, we’re seeing something of a hockey-stick effect – rising from around 110 towards 130 as the dollar became a safe haven for nervous investors and institutions.

US Trade Weighted Exchange Rate (Index Jan 2006 = 100)

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve

Given the IFPI Global Music Report is presented in US Dollars and in constant currency over time, the impact of the dollar’s dominance is two-fold: devaluing the absolute value of the ‘rest of’ the global music industry, and increasing the US’ relative share.

So our first smoke signal is the mathematical impact this fluid exchange rate may have on next year’s Global Music Report for 2022. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume that the US dollar has appreciated against the Yen from ¥110 to ¥130, an increase of 18 percent. Further, let’s assume the Japanese music industry continues to grow at 9 percent this year. The 18 percent collapse in the Yen’s exchange rate, combined with the 9 percent growth in domestic revenues, results in Japan’s USD-denominated contribution to the GMR falling eight percent from what it reported in the 2021 yearbook. Of course, constant currency smooths out the dollar-trend, (year on year change remains nine percent) but there is an absolute drop in the dollar value of the Japanese recorded music industry. This matters, when adding up a global industry and determining its trend.

That takes us to our second smoke signal: the spillover impact on the US share of global collections. In my book Tarzan Economics, I explore an inconvenient truth in streaming (and globalisation more generally): the digital music business has become more global in culture, yet more American in commerce. Since the launch of Spotify in the United States in 2011, the business has gotten bigger (up by more than half) and more American (up from a quarter to almost two-fifths).

US Share of Global Recorded Music Revenues

Source: IFPI Global Music Report, CISAC Global Collections Report, Music & Copyright, MIDIA and Will Page

The world's biggest recorded music market is making the biggest contribution to growth. This year’s RIAA Mid-Year report showed the US growing at an impressive 8% to $4.9 billion – meaning the US market could be worth $10bn by year-end. Add the impact of exchange rates and it's possible that the US could make up half of all global recorded music revenues within the next couple of years. (US publishers may find themselves in the same boat should the Copyright Royalty Board proposed rate increase take hold – an uplift not currently being seen elsewhere). It’s both reassuring and alarming that one country dominates this global success story of music copyright, bringing to mind the old economic adage “when America coughs, the rest of the world catches a cold.”

Acknowledgements

A huge debt of thanks to Chris Carey (Opinium Research) for cranking out the model and David Safir for being the original source of inspiration for this work. In addition, thanks to Adrian Strain and Sylvain Piat (CISAC); John Blewett and Lauri Rechhardt (IFPI); Simon Dyson and Matthew Pougher (Omdia); Mark Mulligan (MIDIA); Anna Clara Olofsson (Epidemic Sound); Tom Frederikse (Clintons); Agnieszka Pustula (Redburn Research); Jimmy Harney (Luminate); Dr Hayleigh Bosher (Brunel University); Shannon Nitroy (Spotify); Bill Gorjance (peermusic); Ger Hatton (Independent Music Publishers Federation), Kris Ahrend (Mechanical Licensing Collective) and many music industry executives from streaming services, labels, publishers, and CMOs who made this possible. Special thanks to wordsmith Sam Blake for copy-editing and Alice Clarke for design and infographics.