How recently have you been invited to take some kind of survey? It likely hasn’t been more than a couple of days.

Our research shows that surveys are among the most commonly used research methods by UX practitioners. Surveys have their place among the various quantitative UX-research methods, but it is more challenging to create a good survey than many professionals think. It is very easy to write a bad survey that gathers flawed data.

Limitations of Surveys

Survey Participants Can Filter Responses

Unlike observational methods, which reveal real-time behaviors that cannot be easily faked or filtered (such as the ease or difficulty of navigating a new mobile app), surveys are self-reported – which means that respondents get to filter everything they share with researchers before they share it. This is a major limitation of surveys, no matter how well they are written — because researchers are generally interested in phenomena as they really occur, not in (intentionally or unintentionally) censored information. Other self-report research methods where users can decide what they share include interviews, focus groups, and diary studies.

Researchers Cannot Probe in Surveys

Another limitation of surveys is that researchers cannot probe to better understand responses. This is because respondents usually complete them without the researcher being present. Even if researchers could afford to watch every single respondent take a survey, doing so would bias the responses and contaminate the data. Moreover, survey responses generally come as ratings on a simple scale or as selections on multiple-choice questions. It is impossible to know why someone responded the way they did without more information (a limitation shared by analytics data). Even if there is space provided for a respondent to type out additional comments, these open-ended responses tend to be brief, disconnected, or skipped entirely.

Surveys Only Collect Attitudinal Data

Surveys collect attitudinal data, representing how users think and feel — not how they behave. They are no substitute for observational methods such as usability testing or analytics, that can accurately reveal user behaviors. Surveys remove respondents from workflows and require them to reflect on experiences and behaviors rather than demonstrate them. For example, even if a survey asks users how often they tend to access a particular feature on a website, it is really asking them how often they think they access that feature. Questions about behaviors do not accurately capture how people actually perform those behaviors; instead, they reveal users’ perceptions and recollections about those behaviors. Use surveys to learn what users think and feel, not what they do.

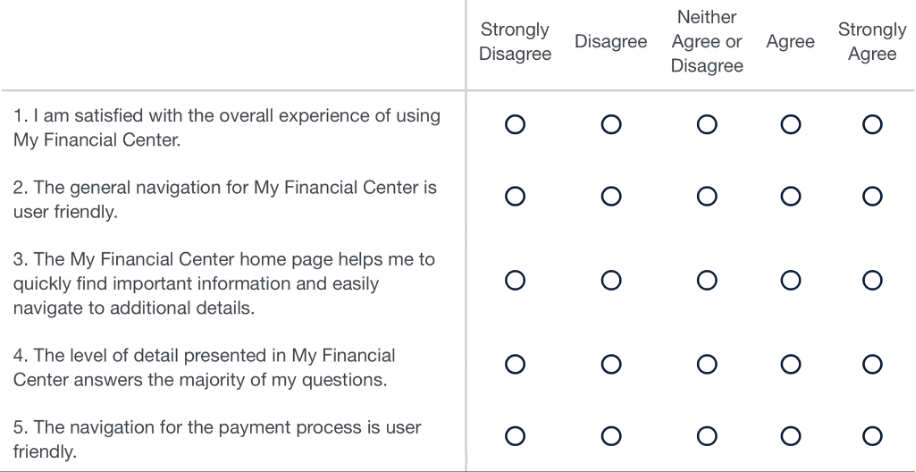

Consider the following excerpt from a survey emailed to university students regarding a financial dashboard for monitoring and paying school-related expenses. The likely purpose of this survey is to gain insights about the usability of the dashboard. Unfortunately, respondents taking this survey are obviously not using the dashboard; moreover, depending on when they used the dashboard, their recollections about the UI will be incomplete, vague, or wrong. As a result, the survey responses cannot accurately reflect how “user friendly” the dashboard is. Research goals investigating usability, findability, discoverability, or other behavioral metrics must be studied with observational methods, such as user testing. Survey data can be used to complement performance-based data, but it cannot, by itself, offer a comprehensive assessment of the usability of a system.

Although developing a good survey can take time and multiple iterations, it is quick and cheap compared to many other research methods — which is why surveys have become so popular. Surveys can be useful for gathering large amounts of both quantitative and qualitative data when researchers are investigating what users think or feel. However, to gather good data, a survey must be written well to be both internally and externally valid. If a survey is not written well, it will produce bad data.

The following 10 points describe common ways in which research participants tend to misrepresent their true thoughts and feelings on surveys. While it is impossible to fully mitigate the effects of these tendencies, there is much that can be done to lessen their effects.

1. Recall Bias

Although people tend to feel that they can accurately remember how things were in the past, they actually forget most of the details as time goes on, and their feelings about things change without them noticing. Imperfect memory presents a great challenge for any survey that focuses on a specific event or experience but is completed after the fact. Observational methods that capture insights as experiences occur do not suffer from recall bias in the same way that surveys do. People are most easily able to remember details about things that were recent, that they think about frequently, and that are associated with strong emotions.

Preventive tip:

Distribute a survey to participants as soon as possible following the event related to your research. For example, if your survey asks why a user subscribed to a particular service, have the subscription act as a trigger for the survey, while their rationale for subscribing is as fresh as possible. Don’t wait to send the survey to large groups of subscribers at once.

(Still, even if you follow this tip, there is no guarantee that people will complete the survey right away.)

Even better, consider using surveys in connection to an observational user-research method such as usability testing. For example, you could show a survey such as the SUS to users who have completed a test of a website. In this way, the experience would be fresh in their mind as they respond to the questions, and you will be able to use the survey-provided attitudinal data to complement other performance-based metrics such as success rates and task times.

2. Recency Bias

Individuals tend to give more weight to recent events than to events from longer ago. When asked about an overall experience or opinion on a survey, it is likely that people will respond based on how they have been feeling lately rather than taking an accurate mental average of their feelings throughout time.

Preventive tips:

Ask about both a recent experience and a previous one. If the research question focuses on opinions and attitudes at multiple time points, then intentionally capture someone’s most recent feelings first, before prompting them to consider how those feelings have changed with time.

Use a longitudinal method (such as a diary study) rather than a survey. If your research question investigates user attitudes or feelings at various time points, have participants respond at those points rather than relying on one survey at the end that will likely be skewed toward more recent events.

3. Social-Desirability Bias

People are highly motivated to conform to societal norms and portray themselves in socially desirable ways. For this reason, participants might (both consciously or subconsciously) distort their answers to be closer to what they think is socially acceptable. For example, they might overemphasize how important environmental sustainability is in their lives because it is increasingly valued by society, or they might underemphasize how much they love a particular indulgence if it is looked down upon by society.

Preventive tips:

Emphasize confidentiality (the researcher knows their respondents’ identity but will not share it with others) or anonymity (not even the researcher knows the identity of respondents) of their answers. Reassuring participants that their responses will not be connected to their identity helps them feel comfortable with being candid and truthful.

Use indirect questioning. This method can allow respondents to be more honest without feeling as strong of a need to conform to societal norms For example, a survey investigating feelings about a particular political candidate might also ask about candidates with similar political views to the candidate in question. Respondents could also be asked to describe how their close friends or colleagues feel about an issue. Open-ended responses are often necessary to capture relevant data in these cases but run the risk of not fully answering the research question.

4. Prestige Bias

People do not like to be negatively portrayed. When given the opportunity, survey respondents tend to distort their responses to make themselves seem more impressive, smart, or successful. Common examples include the tendency to round up one’s income or downplay (or fully deny) negative actions such as violence or abuse. Because surveys are a self-report method, respondents will not always accurately represent their true opinions and actions.

Preventive tips:

When exact numbers are not necessary, provide ranges in response choices. Allowing someone to select a range that includes their true answer is more likely to be accurate than asking respondents to report it directly. For example, providing age or income ranges will avoid requiring respondents to directly input their age or salary and will be less likely to result in a distortion. In many cases, larger ranges increase the chances that someone will provide an honest response (e.g., 65–80 years old vs. 66–70, 71–75, 76–80 years old).

Use other data sources for sensitive data that is critical to your research. Often, researchers find it easier to ask participants to report information about themselves as part of a survey than to collect this data from other available sources. However, sensitive data such as income, weight, or achievements will be more accurate when gathered from another source, if available.

5. Acquiescence Bias

People tend to agree with statements more than disagree. For example, if asked whether they agree or disagree with the statement [Our company] provides high-quality products, a larger proportion of respondents is likely to select “agree” than “disagree,” no matter the company. The tendency to agree is often due to the natural desire to be nice to others; it can also serve as a shortcut and conserve mental energy. It can also be the case that a respondent has no strong reason to disagree and gives the benefit of the doubt, which will generally result in agreement. The acquiescence bias can lead researchers to reach falsely positive conclusions.

Preventive tips:

Ask a direct, open-ended question rather than asking for agreement or disagreement responses to a statement. People will be most likely to report their true feelings when there is no obvious way to simply “agree.”

Use a semantic-differential scale rather than a Likert scale. A semantic-differential scale still asks participants to provide a rating but provides a continuum of response options specific to the nature of the question. There is generally no obvious “agreement” option available.

Include reverse-keyed items. When respondents indicate whether they agree or disagree with multiple similar types of statements in a row, they are more likely to quickly select positive responses to all. Alternating the focus of statements or questions participants are responding to can serve as an indicator of whether the participant was intentionally reading and responding to each individual item. For example, instead of having participants indicate their agreement or disagreement with a series of positively framed statements (e.g., [This company] has my best interest in mind) all in succession, intermix them with some negatively framed statements (e.g., [This company] intentionally tries to deceive its customers). However, reverse-keying items should be done sparingly, only when there are many of the same response types in a row, as it increases the overall cognitive load required to respond and the probability that an error will be made when responding or coding the responses.

6. Order Effect

The order in which response options are presented in a closed-ended survey question (such as multiple-choice or multi-select) affects which options are most likely to be chosen. The options near the beginning and end of a list tend to be the most likely to be chosen because of the primacy and recency effects. (The primacy effect describes the tendency to select the first seemingly satisfactory option a respondent sees. The recency effect describes how the last, or “most recently seen,” option in a list is freshest on the mind and thus, the most easily available for selection.)

The order in which the questions in a survey are presented can also bias responses. Question order can unintentionally reveal the purpose of a survey, might create pressure for respondents to be consistent with themselves, or might cause end questions to be neglected due to survey fatigue.

Preventive tips:

Organize options meaningfully. When options can be ordered meaningfully (e.g., alphabetically, chronologically, locationally, temporally, or categorically), respondents are more likely to quickly identify the options that apply to them rather than simply picking those at the beginning and at the end. This is particularly true with long lists of options that are conventionally listed in a particular order.

Randomize the order of response options. When there is no obvious meaningful order for response options, randomizing their order gives each option an equal chance of falling near the beginning or end of a list. For example, it would be appropriate to randomize the order of different color options, but not ranges of ages.

Randomize questions if possible. If the order of your survey questions is not important, consider presenting them in various orders to different participants to avoid the same initial questions consistently influencing responses on later ones. You can also show questions on separate pages to avoid possible confounds.

7. Current-Mood or Emotional-State Bias

A respondent’s current emotional state will affect how (and whether) they respond to a survey. If someone is feeling rushed, tired, or apathetic, they are unlikely to even begin a survey in the first place, let alone provide meaningful responses. Your first goal when deciding when to distribute a survey is to maximize the response rate. It is unwise to blast out a survey when the majority of potential respondents are likely to be busy (e.g., at the start of a workday), or at a point in the customer journey when someone is dealing with complex problems (conduct a diary study instead to study these complex parts of an experience).

Beyond this initial challenge, as with all research studies, those who take a survey will provide answers based on their current mood. In some cases, the content of a survey itself might induce a particular mood (such as asking about a recent negative experience), while in others the content is neutral. Unlike observational methods, surveys cannot capture the mood of a respondent (even if you have a question about it!) — which prevents this information from being factored into the analysis and conclusions. This is one reason why survey data cannot be interpreted as a perfect reflection of reality. Calculating the statistical significance and confidence intervals for quantitative findings can help account for this variability.

In cases where a survey is meant to capture overall impressions, it is not critical exactly when a participant takes a survey so long as they are able to relax, focus, and think clearly. In other cases (such as with the System Usability Scale, SUS, and the Single Ease Questionnaire, SEQ), the current mood of the participant is a valuable part of the data to be collected. These questionnaires are intended to capture a user’s reactions in the moments following the completion of a whole test or a single task, and thus must be completed while the relevant mood lingers.

Preventive tips:

Conduct a think-aloud test to understand how your survey makes respondents feel. Have a handful of participants take the survey and share how the questions make them feel. This approach is particularly useful when the content of a survey is likely to arouse strong emotional reactions (for example, if the survey is asking about a difficult experience or a controversial topic).

Encourage participants to take the survey in a particular mood. While this is unrealistic for a simple Net Promoter Score (NPS) that pops up in an email or notification, for longer, more significant surveys it can be valuable to encourage participants to set aside a time when they can focus and relax — particularly when you will be paying them an incentive.

Utilize customer-journey maps to identify opportunities for survey distribution. Just like fishermen studying the fish they intend to catch to know the best time and position for casting nets, researchers must also be intentional about the time and manner in which they distribute surveys. Customer-journey data can help a researcher to understand the current moods of users as they interact with the organization. However, there is obviously no way to predict the personal life circumstances of each participant.

8. Central-Tendency Bias

People are often hesitant to provide extreme responses on rating scales. When survey respondents are asked to select a response on a scale, they often lean toward the middle, no matter how many points there are on the scale.

Because of respondents’ hesitancy to select the extremes (even if their circumstances likely merit such responses), large sample sizes generally lead to somewhat normally distributed data on rating scales. Response scales with an odd number of options inevitably have a middle point which is often labeled as “neutral” or “neither agree nor disagree.” While this middle option is a legitimate response, it also becomes an easy “out” for respondents who don’t want to spend the effort necessary to formulate a true response to the presented statement.

Preventive tips:

Use an even number of response options to encourage participants to lean one way or the other. Receiving many neutral responses will not end up being very helpful for researchers. If a neutral option is needed during analysis, the middle two points can be combined.

Use as few points on the response scale as are meaningful. You only want to have as many points on a response scale as are legitimately distinct and meaningful for the question you are asking. Simply having more points on a scale (such as 7 or more) does not guarantee you will be able to capture more nuanced and informative data. The differences between the responses to options such as “Very strongly agree” and “Strongly agree” on a 9-point scale will mean very little because participants are unlikely to have such specific feelings about most topics. We recommend using a 4-point or 6-point scale in most cases because they are straightforward to answer and analyze, and will capture most meaningful differences.

9. Demand Characteristics

When participants in any type of research study become aware of the researcher’s aims and objectives, they are more likely to change their behaviors or responses accordingly. Participants might respond in specific ways in order to influence the outcomes of the study. This is particularly true when it can be personally beneficial to respond in specific ways. For example, professional participants might try to respond to recruiting screeners (which are a type of survey) in ways that might increase their chances of being selected for a study — regardless of whether they are a good fit.

Some participants intentionally provide extreme or untrue responses if they have some reason to be frustrated with the distributor of the survey, the organization associated with it, or the aims of the study.

Other participants (especially those with strong brand loyalty and positive feelings towards the survey distributor) might try to provide the responses they think the researchers are looking for out of goodwill, attempting to be “helpful.” This also tends to happen when respondents have a personal tie to the researcher — which is why it is important to recruit real users rather than colleagues or friends for any good research study.

Preventive tips:

Hide the true purpose of the survey. Avoid putting too much detail about the purpose of the survey in introductory materials such as emails, notifications, or survey titles and descriptions. It is also wise to mask any response options or survey questions that are critical to the purpose of the study by placing them among other plausible, but less critical options and questions.

Distribute the survey to various types of users. Distributing a survey to users who have had both positive and negative experiences, as well as those familiar and unfamiliar with your brand can potentially offset the demand characteristics described above.

10. Random-Response Bias

When survey respondents do not know the answer to a question, they generally just guess. This is problematic because guessed responses are not accurate data but are impossible to identify. For example, if a survey asked how much time was spent researching a product before purchasing, respondents are likely to just guess since they have no way of accurately knowing — especially those who spent multiple days or weeks researching.

Respondents may also engage in guessing or selecting arbitrary options when they become fatigued or simply want to finish a survey for the offered incentive.

Preventive tips:

Provide an alternative response for those who do not know the answer. Closed-ended survey questions do not allow respondents to indicate that they do not have a meaningful response unless an option such as “none,” “other,” or “not applicable” is provided. However, it is not necessary to provide such options on all questions if it is likely that all respondents will have a meaningful answer. These types of alternatives are an easy way for people to opt out of responding, without fully considering the question (another reason not to have “neutral points in the middle of your scales).

Include reverse-keyed items. Respondents who answer randomly often select the same option for all similar types of questions. Including reverse-keyed items can help you recognize when a participant answered quickly or randomly, without reading the questions. Once again, however, this should be done sparingly, and only when there are many of the same response types in a row.

Keep surveys short. If respondents start guessing because they are getting bored or tired, your survey is just too long.

Conclusion

A well-designed survey can quickly and inexpensively gather many valuable insights, but even the best surveys are subject to response biases. Much of what we know about large groups of people has been gathered through surveys. However, surveys are not always the right method for gaining valuable UX insights and making improvements to digital designs. All survey data must be analyzed with a critical eye and not simply accepted as the truth.

Reference

Davies, R. S. (2020). Designing Surveys for Evaluations and Research. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/designing_surveys