A memory came to mind recently of opening presents after my seventh or eighth birthday party – the thrill of the smooth, sharp-edged wrapping paper as I ripped it open, the breathless discovery of the gift concealed within. I also remember the many dull hours in the days that followed, writing thank-you letter after thank-you letter to grandparents, aunties, neighbours and friends, my mother sitting beside me, addressing the envelopes.

This could be why the notion of formalised, prescribed and premeditated gratitude, which in the past decade has become the darling of positive psychology and the self-help movement, tends to stick in my craw. So, too, the piles of gratitude journals displayed in gift shops among other tat, bespattered with cheesy quotations at jaunty angles: overcompensatingly “inspirational” gifts for uninspired givers on a deadline. Even hearing the word “gratitude” makes my shoulders tense and my eyes narrow. I am too cynical to get on board this particular Oprah bandwagon – too British, too atheist, too sensitive to schmaltz.

But gratitude’s currency continues to increase in value. A “wall of gratitude” was erected in Sheffield last month, built with bricks that each contained a personal message written by local residents expressing appreciation for something important in their lives. Dr Fuschia Sirois, a psychologist at the University of Sheffield who is running the project, explains that a scientific consensus has developed in the past 10 years that undermines my instinctive cynicism. For Sirois and other researchers in this field, gratitude is far more than a slogan on a mug – it is a unique predictor of wellbeing, a protective cloak that could help shield those who feel it from poor mental health.

Study after study has found a robust association between higher levels of gratitude and wellbeing, including protection from stress and depression, more fulfilling relationships, better sleep and greater resilience. Simple exercises that people can do on their own – such as spending two weeks writing a daily list of three things for which they are grateful – have been found to increase life satisfaction, decrease worry and improve body image, with the beneficial effects lasting for up to six months. Robert Emmons, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Davis, and a world authority on gratitude, has advocated that interventions such as this be used by therapists to help their patients.

Gratitude was one of the most powerful variables that personality psychologists could find when it came to predicting wellbeing, over and above most known factors, from wealth and health to other personality traits such as optimism, Sirois says. “There is something very special about gratitude. It is something wholly unique, unto itself, that, from a statistical standpoint, rises up to the top of the milk, like cream,” she says.

But why? What is it about this emotional experience that has such a miraculous impact? How does it work? “I think that’s something the field is still trying to unravel. We don’t yet know what the black box is that links gratitude to these wonderful wellbeing outcomes,” she says. Faced with such unequivocal research findings, my contempt seemed foolish and arrogant, so I decided to swallow my scepticism and give gratitude a go.

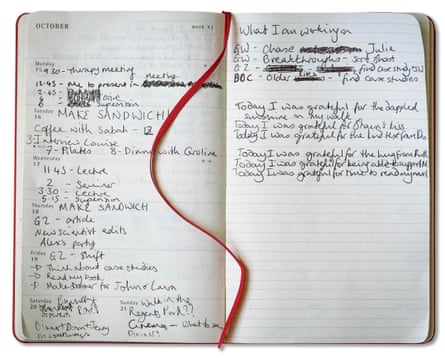

I couldn’t bring myself to buy one of the journals with a corny saying on the cover, so I used my regular diary. The first night, I struggled to work out exactly what I was supposed to be writing and simply noted some good experiences I had had that day. But that did not seem quite right – I was pleased these things had taken place, but I did not feel what Sirois described as an “overwhelming feeling of appreciation”.

The next night I adapted my method and wrote the words “Today I was grateful for”. As I pondered what to write next, I felt a warm, settled, comforting feeling in the pit of my stomach. Over the following weeks, I was at various times grateful for the time to read my book, grateful to my husband for cooking me soup, grateful to feel the stretch of my muscles in my pilates class. I began noticing things to be grateful for as they happened, mentally filing away the moment for that night’s gratitude list. My husband grew used to drifting off to sleep, only to be woken 10 minutes later when I crept out of bed, having realised suddenly what I had forgotten; I suspect that, at those moments, any increase I experienced in gratitude was offset by a decrease in his.

As the pages in my diary filled up with scribbled gratitude, I started to find the concept less vomitous. But there was still much that left me uneasy about the way gratitude has been rebranded by personalities such as Oprah, Arianna Huffington and Richard Branson as the key for everyone to unlock a successful relationship, career and lifestyle. For some people living in poverty, or who have suffered discrimination, or who have a history of trauma, or whose mental or physical health problems have had a devastating impact, to be told that trying to feel grateful might help may feel like an insult.

There may be people for whom keeping a gratitude diary could be counterproductive, says Alex Wood, a psychologist and the centennial professor at London School of Economics who has been a major contributor to this field. There is caution in his voice as he points out that there has been little research into what he calls “the dark side of gratitude”. He says: “The blanket endorsement of gratitude has been too early in the field. I’m suspicious of any claims you should put this into practice on the basis of a few studies, or that this should be used on vulnerable populations such as people with depression.”

Some people may find it helpful, Wood says, but it is feasible that others could feel a sense of misplaced gratitude that keeps them trapped in a dangerous situation, where instead of recognising their reality they feel a perverted form of thankfulness towards those oppressing them. “Many people might feel a lack of gratitude because they’re in objectively bad situations. For people in abusive relationships, for example, the answer is to get the hell out, rather than feel more gratitude,” he says. To have a positive impact, it cannot be indiscriminate – it must be “gratitude with discernment”.

Scientists cannot yet tell us where, how or why gratitude develops in the brain, says Wood, but he references the economist and philosopher Adam Smith’s theory that it has an evolutionary purpose. Smith argued that society only works if we repay the aid that we get from other people, but since we have no legal or financial incentive to do so, we have evolved a sense of gratitude that makes us do it. “If we’ve naturally evolved to feel it, that rather flips the question from what causes gratitude to what causes ingratitude – why do some people not have the capacity to feel it?”

If someone has grown up in an environment in which they cannot rely on the people who are meant to take care of them, in which their need for love is met with neglect and abuse, Wood says, “I think it would be very difficult for them to experience gratitude, with that particular lens through which to view the world”. In that situation, says Tomasz Fortuna, a psychoanalyst and psychotherapist at the Tavistock and Portman NHS trust, “what gets mobilised instead is a sense of threat, a fear of annihilation and the feeling of being persecuted, deprived”.

To have the capacity to feel gratitude, Fortuna says, you must be able to receive and accept something helpful or good from another person. It helps if this is something you see happening around you from infancy, so you can learn how it works.

It seems to me that a lot of things need to go right for a person to have the capacity to feel gratitude – it is a pretty advanced-level emotion. If feeling grateful to someone else is at least partly contingent on having had healthy, nurturing, nourishing relationships in early life, if it means being able to tolerate feelings of vulnerability and being able to value something given to you by someone else without feeling envious, it is hardly surprising that there is a correlation between gratitude and wellbeing. Hearing this, I felt an instinctive and overpowering sense of appreciation for what my parents gave me as they made me write those thank-you letters. I tried to remember to add it to my gratitude list that night.

That is not to say that gratitude cannot develop in later life. At the Portman clinic, Fortuna works with adults who have problems with violence, many of whom had an extremely disturbed, traumatic upbringing. At first, he says, it is not unusual to see very little gratitude from patients, either towards their therapist or towards others. But when a patient begins to feel understood, there can be a shift. “You can sometimes see very small things – a patient appreciating something someone else did for them, like a smile from a shop assistant or a friendly, caring tone of voice on the phone. Suddenly, the patient, who has felt for a long time that everyone is threatening and that they are being persecuted, discovers something friendly in an interaction.” That is a sign of gratitude where none was seen before and it can be a pivotal moment in therapy, Fortuna says. “You can see the emotional development of a person; their internal world becomes more enriched, more balanced. It gives us a sense that this work is worthwhile.”

This gradual emergence of profound moments through meaningful encounters feels different from the branding of gratitude as a lifestyle choice. There are times when I have to force myself to write my gratitude diary and it feels like a capitalistic stockpiling of emotion, as if I am making deposits into my gratitude savings account, accumulating moments of appreciation to build myself a richer life. Fortuna fears that, in some cases, this kind of exercise could be counterproductive. “I think this could become a kind of positive thinking, where we try to convince ourselves, to reassure ourselves that things around us are good. There is falsehood in this; it’s an illusion.” Having the capacity for gratitude, he says, is about having faith that you do not have to earn everything yourself.

Nevertheless, after four weeks of counting my gratitude, I think I will keep doing it – for as long as I remember to, at least. I sometimes find that, before bed, my thoughts speed up into an anxious whirl; concentrating on what has brought me gratitude that day seems to quieten my mind. I am also finding more things to be grateful for as they happen – it is a useful tool for reflection, for noticing things I might otherwise take for granted.

While the diary has helped me in some ways, I am no evangelist. As Wood says, there have not been enough studies to prove that the relationship between gratitude and wellbeing is causal, rather than correlated. We should be wary, he says, of leaping to conclusions about how a gratitude diary can improve mental health: the positive effects may be partly explained by the act of doing something for oneself, with hope and optimism.

There have been moments of gratitude in my life that have been transformative and they have all been spontaneous. I have felt it while volunteering at The Listening Place, a charity for people who are suicidal, where I listened to a visitor as she told me the story of her life. I felt the privilege of bearing witness to another human being’s trauma when she needed me to. I have felt it with my husband, when in moments of acute distress I have not known what I needed, but he has. I have also felt it in psychoanalytic psychotherapy, when my therapist has seen and understood me in a way I have never experienced before; she has helped me towards the painful realisation that I have unknowingly limited my experience of life through my thoughts, feelings and reactions.

At these moments, gratitude has made me feel as if I am experiencing a new layer of life. While keeping my diary has been helpful, at times I have ended up with something that looks like gratitude and sounds like gratitude, but feels like something flatter, just words accumulating on a page – a thank-you letter a child has been forced to write. I remain sceptical of the commodification of gratitude, suspicious of the conclusion, so easily drawn, that if you do not feel grateful it is because you are not trying hard enough – you have not done your gratitude exercises, along with your downward dog and your mindfulness practice and everything else we are supposed to do to perfect ourselves.

It is comforting to think of our feelings as being within our control, like a muscle to be trained, only with a notebook and pen. But I believe the reality is more arduous and more luminous. Significant and enduring psychological shifts take time, hard work and, crucially, help from other people, sometimes professionals. The shameful under-funding of mental health services means that many people do not have access to treatment. But when we do get the help we need, real change can become possible. That is a beautiful idea, one that has made me feel truly grateful for being in the world – and I could never have come to it alone.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion