Customer-journey maps visualize a user’s journey towards a goal, usually over time and across channels.

In its most basic form, journey mapping starts by compiling a series of user actions into a timeline. Next, the timeline is fleshed out with user thoughts and emotions to create a narrative. This narrative is condensed and polished, ultimately leading to a visualization used to align stakeholders on the holistic experience and identify opportunities for optimizing and improving the journey.

Depending on context, existing resources, and project scope, the journey-mapping process can be approached in number of ways. We surveyed 343 practitioners who create and use journey maps in order to understand the following:

- What kinds of experiences are practitioners mapping?

- How does user research inform the journey-mapping process?

- Who is involved in creating journey maps?

- How do practitioners identify and align on journey-mapping components (e.g., actors and journey phases)?

What Kinds of Experiences Are Mapped?

Short answer: Journey maps are most frequently used to evaluate existing experiences. The majority of journey maps focus on active product (or service) usage or end-to-end customer journeys.

Journey mapping can be used as a process to evaluate and optimize existing products or services or as a visioning exercise for future-state experiences with products and services that don’t exist yet.

Our research indicates that, most frequently, practitioners use journey mapping to explore products and services that already exist — either to evaluate the current experience of those existing products (89%) or to envision optimized, future-state experiences with existing products (73%). Still, over half or respondents (61%) indicated that they also use journey mapping to brainstorm future-state experiences with potential new services or products that do not yet exist.

Journey maps can be used to evaluate experience at the customer-relationship and -lifecycle level or they can zoom in to explore activities related to specific goals.

Our research indicates that, while practitioners use journey maps to explore various types of journeys, from presales experiences to purchasing and onboarding, active product or service usage and end-to-end journeys are the most frequently explored (71%). Support receives the least attention: only 26% of respondents indicated they use journey maps to understand these types of journeys.

How Does User Research Inform Journey Mapping?

Short answer: Most practitioners employ a hypothesis-first approach. User interviews are the most utilized method; diary studies are the least.

When creating a journey map, there are 2 high-level approaches for how to begin.

- The research-first approach begins with a designated period of primary user research led by the UX or design team; the research is later consolidated into a map.

- The hypothesis- or assumption-first approach begins with a workshop where a crossfunctional team makes use of existing knowledge in order to create an assumption map or hypothesis map.

The majority of practitioners (62%) use a hypothesis-first approach, relying on already existing knowledge held by team members or stakeholders to being the mapping process. About a third (35%) of practitioners begin the mapping process with an upfront user-research phase.

Beginning a journey-mapping project with a hypothesis-first approach often makes sense for teams who need to lower the entry barrier to mapping and get multiple parties engaged, move quickly due to a condensed project timeline or limited resources, or who have existing research insights available and do not need to invest in extensive upfront research.

If you begin with a hypothesis-first approach to build buy-in with stakeholders, we recommend following up this stage with user research to validate or evolve assumptions and create a second version of the map that integrates primary user-research findings.

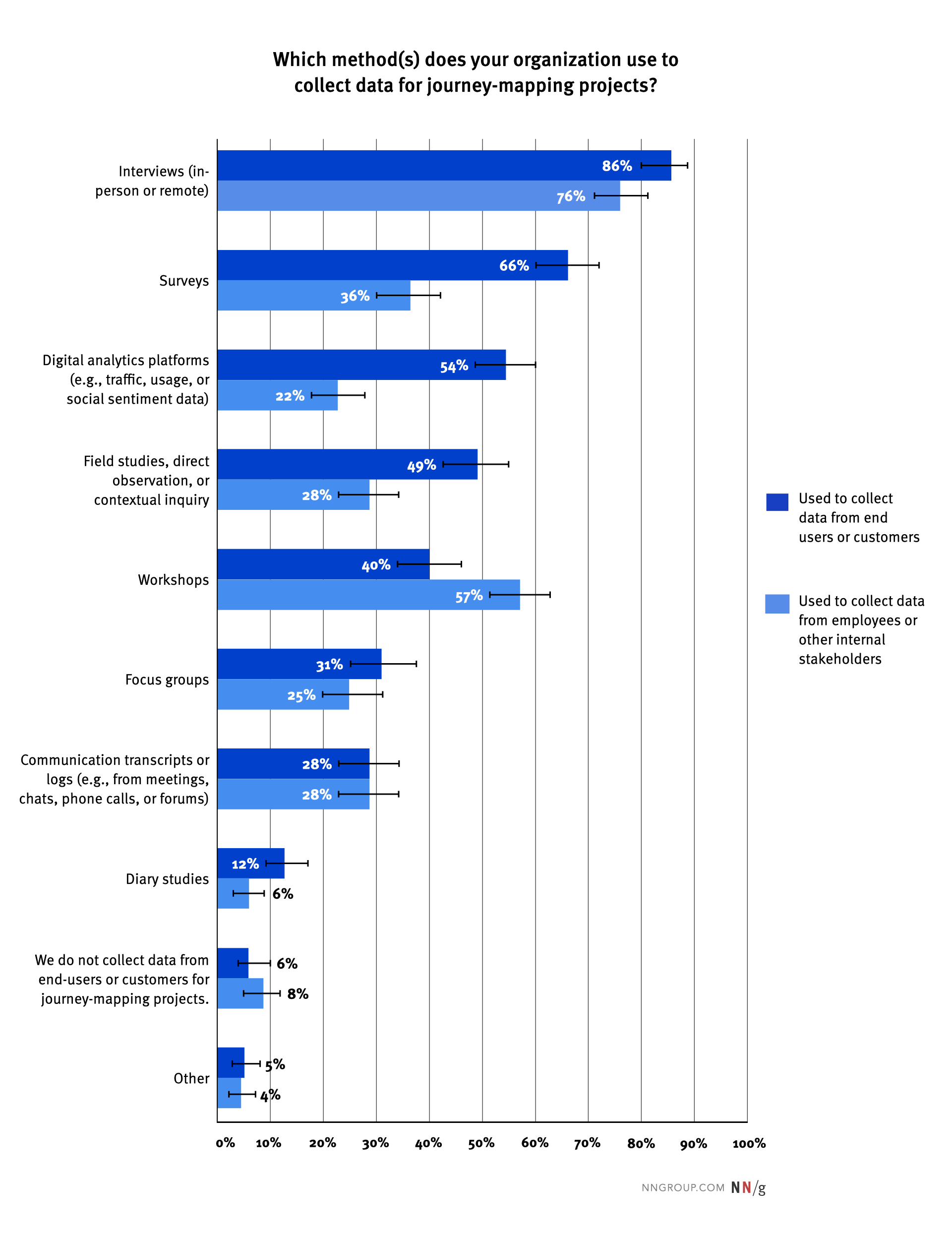

When it comes to specific research methods for journey mapping, interviews are the most utilized method — 86% of respondents used them for external user research and 76% for internal stakeholder research.

Interviews are generally a great research method for informing journey maps: They reveal first-hand stories about customers’ experiences, mindsets, and actions, and they are usually easy to conduct and flexible in format (e.g., can be conducted remotely or in person).

Diary studies are utilized the least — only 12% of respondents reported using them for external research and 6% for internal research. That’s a shame. Because customer journeys happen over time and across many different channels, diary studies are a particularly useful method for understanding users’ thoughts, feelings, and actions over time. They can be coupled with user interviews to better understand key milestones and more in-depth attitudinal data.

Who Is Involved in Creating Journey Maps?

Short answer: Most journey maps are cocreated by a team of multidisciplinary roles who contribute and collaborate via physical or digital tools.

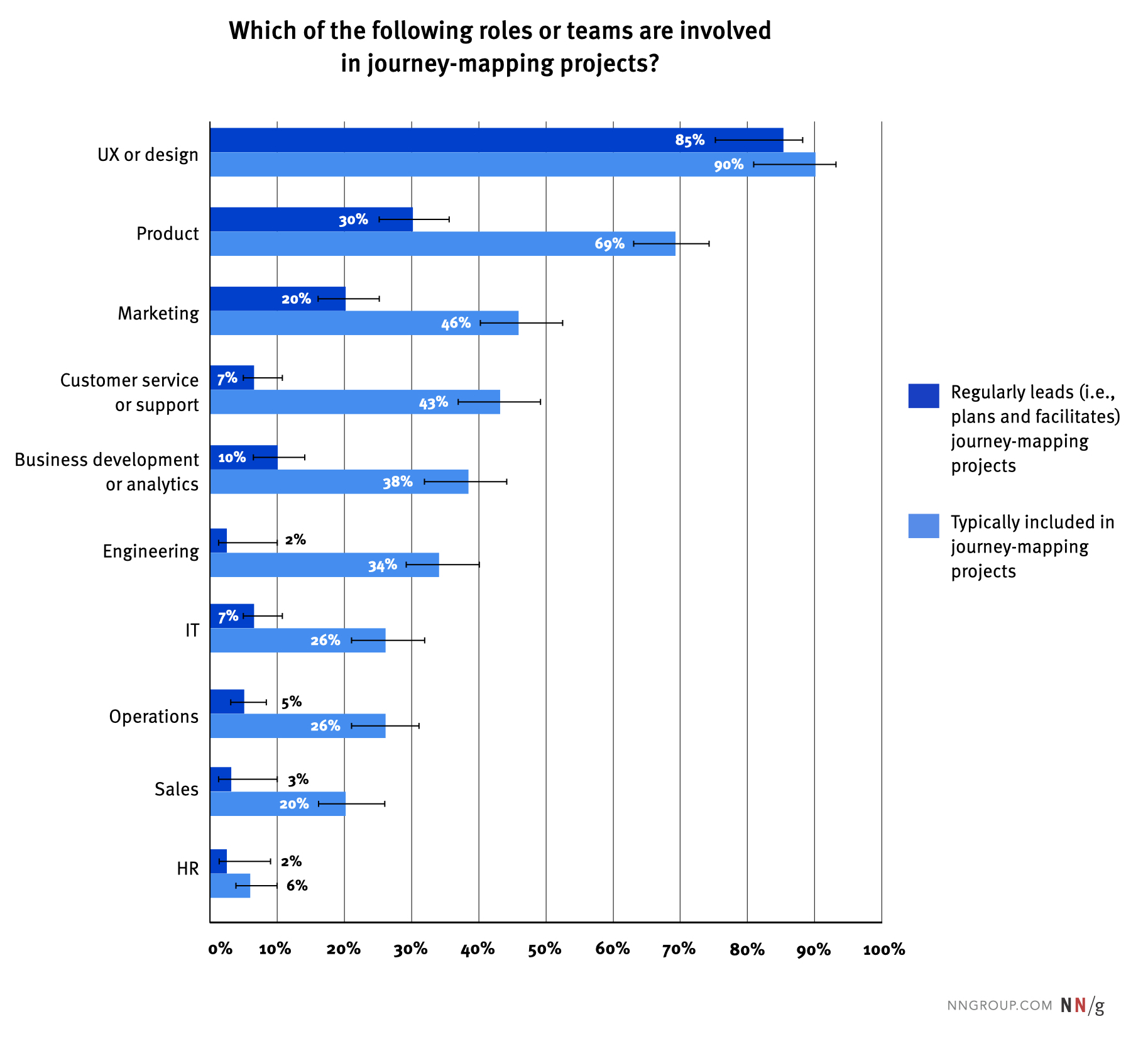

In our study, UX or design roles were most commonly indicated as either leads or contributors for journey-mapping projects. Of course, our sample population is highly biased, as we recruited from our own audience of readers.

What’s more interesting is the fact that journey mapping is typically a highly collaborative process, frequently involving crossdisciplinary roles from product, marketing, and customer service or support, 70%, 46%, and 42% of the time, respectively.

Involving representatives from various departments or lines of business is a smart approach. These groups often have ownership and vested interest in the success of segmented portions of the customer journey. Bringing them together builds collective knowledge and a more comprehensive understanding of existing pain points and opportunities.

In addition, most practitioners (64%) reported creating the journey maps collaboratively, with 34% collaborating over physical tools (e.g., sticky notes and paper) and 30% using digital tools (e.g., Miro, Mural, Google Sheets). In contrast, 36% reported creating the map as a solo activity using either physical tools (10%) or digital tools (26%).

How Are Journey-Mapping Components Identified?

Short answer: Existing personas are often used as actors, while journey phases are creating during the mapping process.

Journey maps rely on certain components to organize the narrative and ensure that the artifact is easy to understand and process. These components can be identified either at the initiation of the journey-mapping project or during key milestones within the journey-mapping process, such as research phases and workshops.

One component is the actor, which generally aligns to a user group or persona and helps answer the question, “Who is this journey map about?” Most of our respondents (49%) used existing personas for their journey-mapping projects. Less than a third (27%) developed personas as a part of project-related user research and even fewer (14%) created personas during a project-related workshop phase.

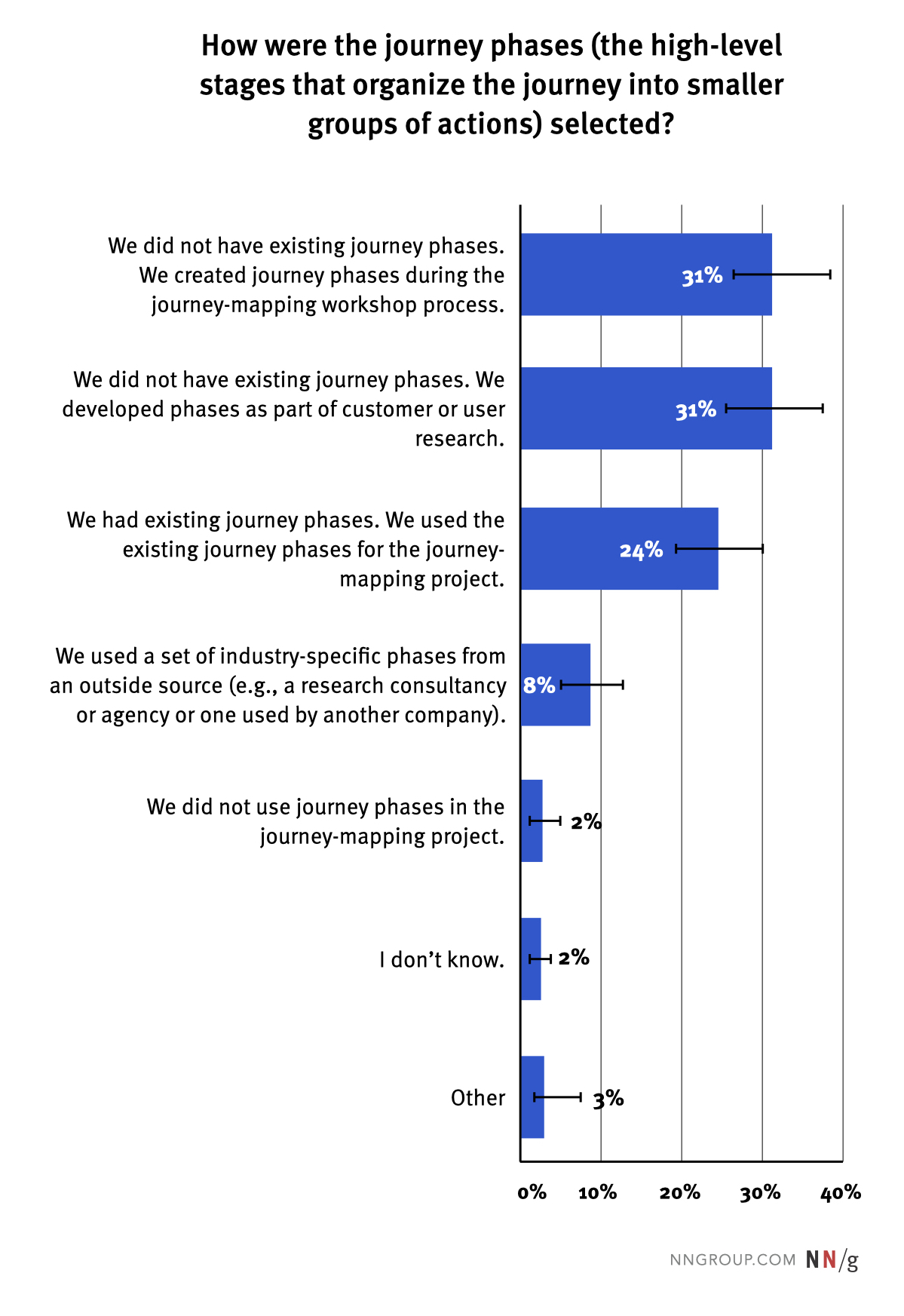

Another component is the set of journey phases that describe journey subgoals and help organize the doing, thinking, and feeling content within the map. In contrast to the actor, most respondents reported that they did not begin the journey-mapping process with phases identified; instead, they either identified them during user research (31%) or during a workshop (31%).

This finding is not surprising; while some larger organizations might start with a strawman set of phases borrowed from a marketing or sales lifecycle, it is also appropriate to let phases emerge as internal knowledge consolidates and external research reveals unknown gaps.

Conclusion

While there are varied ways to shape and conduct journey-mapping projects, our research indicates some common trends.

During journey-mapping projects, practitioners in our study typically:

- Used journey mapping to understand the experience of existing products and services

- Relied on interviews as a primary research method

- Used a collaborative process to create journey maps

- Involved contributors from multiple departments

- Used existing personas for their maps

- Created journey phases during the mapping process

If you’re determining the appropriate approach for a specific journey-mapping project, consult the following resources:

- How to Conduct Research for Customer Journey-Mapping: 5 types of research methods appropriate for journey mapping and how use them together

- Journey Mapping: 2 Decisions to Make Before You Begin: When to use an assumption-first approach vs. a research-first approach, and when to use current-state vs. future-state journey maps

- The 5 Steps of Successful Customer Journey Mapping: 5 high-level steps to journey mapping and how to scale them for your project scope and timeline

- How Much Time Does it Take to Create Customer Journey Maps?: Data for understanding and estimating the time and cost involved in the journey-mapping process